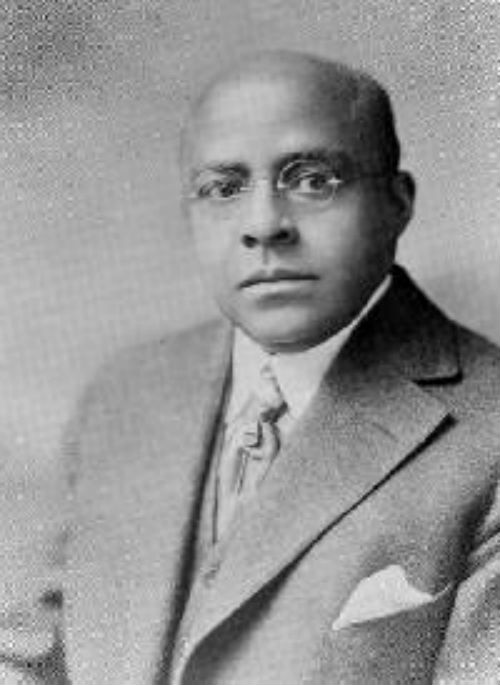

Philip Payton Jr. was not a musician, not a poet, not a painter of portraits, or a sculptor of figures. He was an architect of space, a dealer in possibilities, a capitalist whose currency was land and whose strategy was disruption. In the Black American saga, we are often told of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Duke Ellington, yet the prologue remains unspoken. How did Harlem become the capital, the pulsing nerve center of American culture? The answer, like so many buried in the margins of history, traces back to a man who dared to make racism too expensive to sustain. Payton is one of my favorite people to teach about because his work exemplifies the power of economic strategy in the fight for Black liberation.

Harlem did not simply become Black. It was made Black through the deliberate, surgical dismantling of economic barriers, a lesson in power brokered through property. Payton understood the American paradox, that capitalism could be both the enemy and the unlikely liberator of Black people. His belief mirrored that of another maligned and misrepresented man, Booker T. Washington.

Washington, often cast as the foil to W.E.B. Du Bois, was not merely the accommodationist history books have flattened him into. He, like Payton, was a pragmatist. He saw economic self-sufficiency as a necessary foundation for freedom, not an end to struggle but a means of sustaining it. Payton’s real estate maneuvering was a street-level application of Washington’s ethos, power not through rhetorical combat but through ownership, through the cold, hard arithmetic of profit and loss.

Harold Cruse, the iconoclastic historian and author of The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, recognized that cultural movements without economic underpinnings would always be vulnerable to erasure. Harlem, the Harlem that birthed the Renaissance that incubated the minds of Baldwin and Malcolm X existed because men like Payton fought to carve out space for Black people to breathe, to own, and to exist beyond the margins. The arts were the flower, but Payton was the soil.

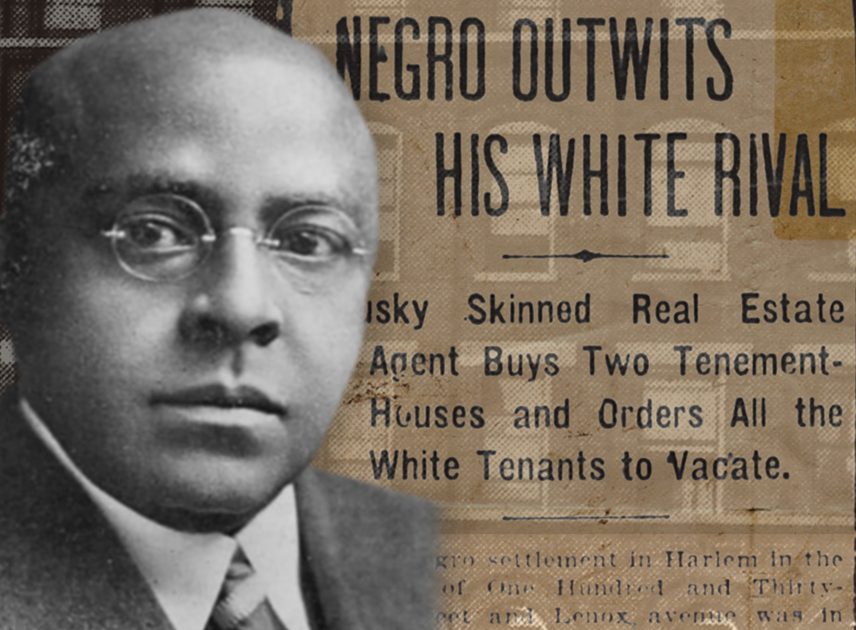

In 1905, Payton’s moment came. A petty dispute between two white landlords, one seeking to punish the other, opened the door for Black tenants to move onto West 99th Street. When the inevitable exodus of white residents followed, Payton saw not tragedy but opportunity. He acquired building after building, block after block, making it impossible for white real estate speculators to reverse the demographic tide. His most famous confrontation came against the Hudson Realty Company, a colossus of white capital backed by men of influence, including the co-founder of Bloomingdale’s and former U.S. ambassadors. When they sought to buy out Black buildings and restore racial purity to Harlem, Payton countered with the same ruthless efficiency. He bought their buildings, evicted their white tenants, and moved Black families in.

His philosophy was simple, force the market to choose between racism and revenue. “Race prejudice is a luxury,” he wrote, “and like all luxuries, can be made very expensive in New York City.” Payton turned the very weapon of segregation, property exclusion, against its wielders. When white landlords locked themselves into restrictive racial covenants, he showed them that racial purity came at a financial cost. Black tenants, long overcharged and underserved, were willing to pay. Slowly, surely, the walls came down.

Yet for all his accomplishments, Payton is a ghost in the halls of history. No statue stands in his honor. No plaque marks the space where he made Harlem Black. He remains an asterisk, an afterthought in a story too often told without its economic prelude.

His legacy, like Washington’s, complicates the myth that capitalism has been solely an oppressor of Black America. It reminds us that economic agency has been both shield and sword in our survival. Washington’s emphasis on self-sufficiency was not submission, and Payton’s financial gambits were not just business, they were battle.

Today, Harlem is gentrifying, the same streets Payton claimed now pricing out the descendants of those he fought for. The cycle repeats itself. History whispers in its undertones, the fight was always about control, not mere presence. The true tragedy of Harlem is not simply that Black people are being pushed out. Payton’s lesson that ownership is the only real defense against displacement was not passed down with the poetry and the music.

Harlem, the Harlem we remember, was not a miracle. It was an investment. Payton paid the price of prejudice so that others could live beyond it. He should never be forgotten.