Jason Whitlock’s latest monologue on Black quarterbacks winning the Super Bowl is a masterclass in deliberate historical amnesia. He wants to act like the quarterback position has never been a racial battlefield. He ignores that Black quarterbacks were told they were not smart enough to lead an offense. Their presence on the biggest stage is a testament to a long-overdue correction of historical wrongs.

The Flawed Percentage Argument

His central argument is that Black quarterbacks winning 11% of Super Bowls roughly aligns with Black people making up 12% of the U.S. population. He claims this proves that racial barriers in the position are a relic of the past. This argument only works if one erases the entire history of Black men being systematically shut out of playing quarterback. Football is not a random lottery. It is a sport where position placement has been dictated by decades of bias, power structures, Additionally institutional gatekeeping. A more honest metric would compare the percentage of Black Super Bowl-winning quarterbacks to that of Black players in the NFL, which has hovered around 65-70% for decades. This number makes it clear that progress is still necessary.

The percentage argument also conveniently ignores how Black quarterbacks were historically forced to play other positions. Teams drafted them as wide receivers, defensive backs, or running backs, even when they had successful college careers at quarterback. This was not a case of fair competition. It was a systemic effort to keep Black players out of leadership roles. Heisman Trophy winner Charlie Ward was told to switch positions or play another sport. Instead of being given a fair shot in the NFL, he played in the NBA.

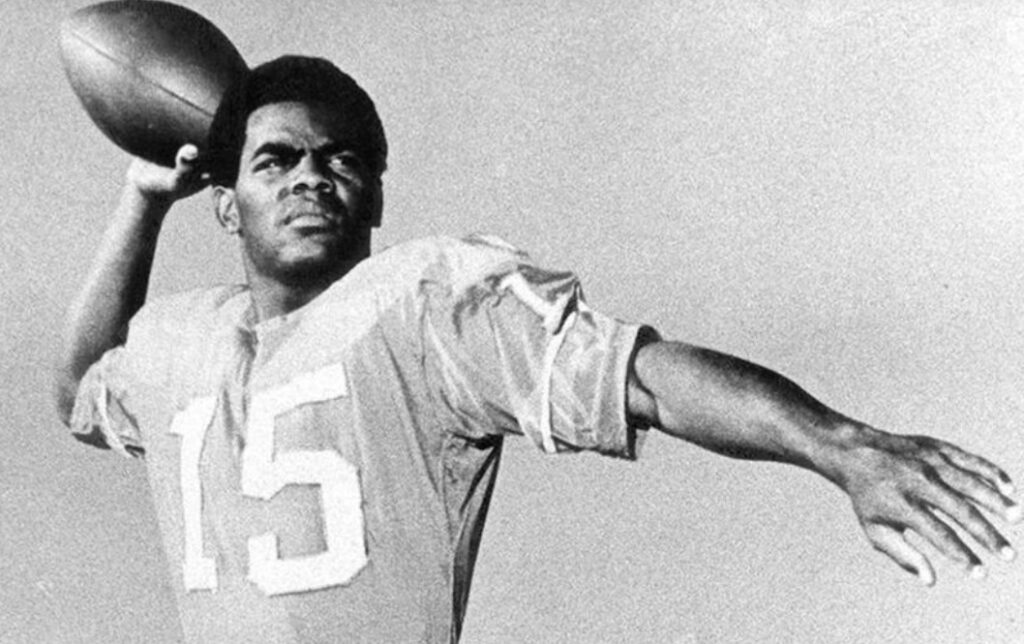

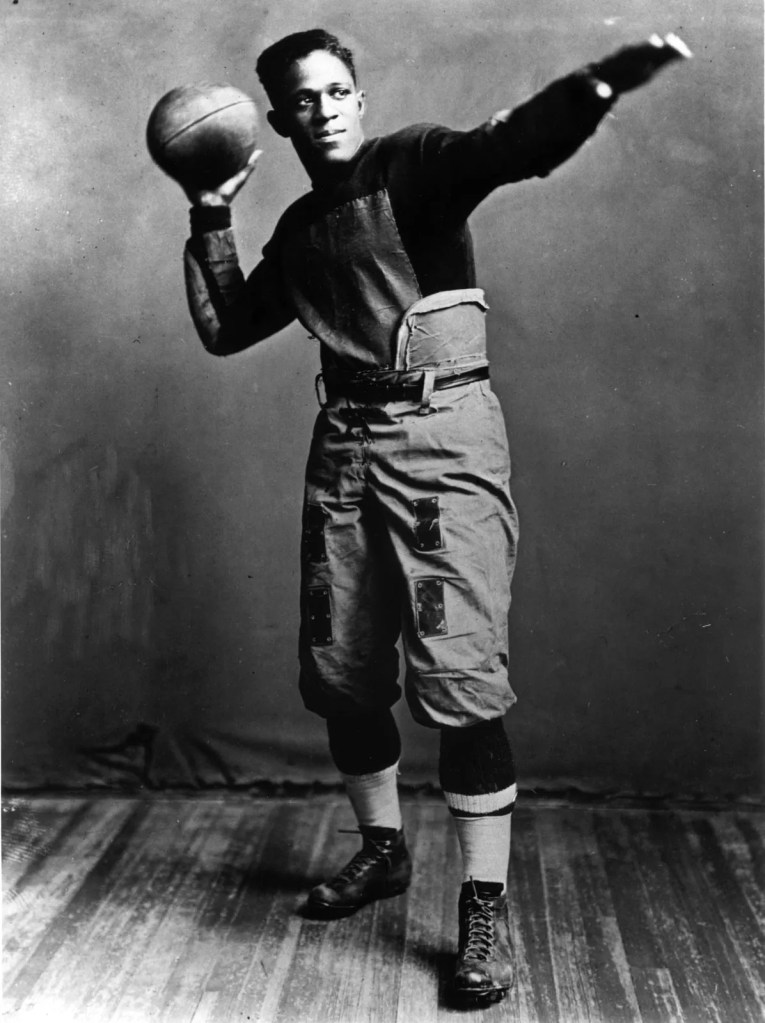

Other examples reinforce this pattern. Tony Dungy, a successful college quarterback at Minnesota, was converted to defensive back in the NFL. Condredge Holloway, the first Black quarterback to start in the SEC, was also pushed away from the NFL quarterback position. HBCU legends like Eldridge Dickey, the first Black quarterback drafted in the first round in 1968, was never allowed to play quarterback and was moved to wide receiver. Even more recently, Terrelle Pryor, who played quarterback at Ohio State, was converted to wide receiver upon entering the NFL. These players were denied opportunities not because of talent but because of the league’s institutional resistance to Black leadership under center. If the playing field had been truly level decades ago, the percentage of Black Super Bowl-winning quarterbacks today would be far greater.

Historical Context Cannot Be Ignored

Whitlock dismisses history because acknowledging it would force him to admit the very thing he is speaking against. Celebrating Black excellence in quarterbacking is not about making everything about race. It is about recognizing the dismantling of a long-standing racial barrier.

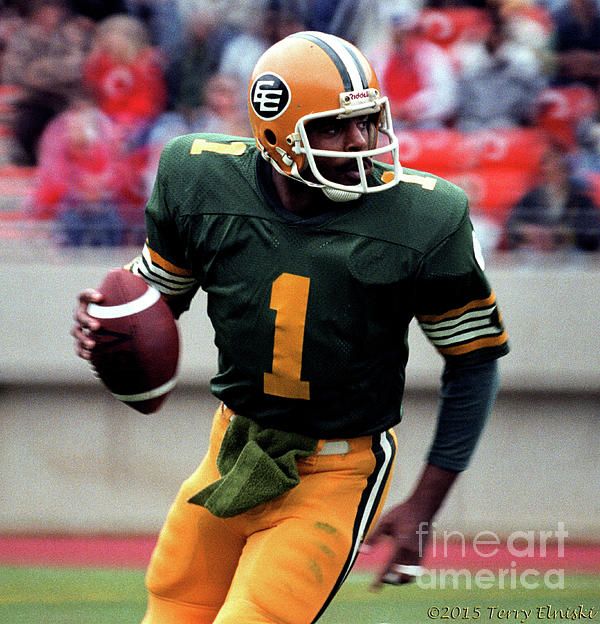

He knows the history. He knows that Black quarterbacks were funneled into other positions because coaches and executives believed they could not lead a team. He knows that Warren Moon, one of the best quarterbacks to ever play the game, had to go to Canada first because the NFL refused to give him a chance. He knows that Doug Williams winning the Super Bowl was not just a great sports moment. It was a cultural earthquake. The idea that everything is already equal is laughable when Black quarterbacks are still routinely forced to answer questions about their intelligence and decision-making in ways their white counterparts are not.

When Does it Stop Being History?

Whitlock sarcastically asks, when does it stop being history? The answer is simple. History stops being history when it is no longer recent. Young Black quarterbacks still have to answer coded questions about their natural athleticism. In contrast, white quarterbacks are praised for their football IQ. Black quarterbacks are still disproportionately asked to switch positions before they even reach the NFL. There is still an annual debate about whether a Black quarterback is truly elite in a way that white quarterbacks never have to endure. The legacy of skepticism that kept Black men from leading teams for decades remains. Lamar Jackson, a former MVP, continues to face analysts questioning whether he can really throw.

The argument that history should be ignored once progress is made is dangerous. Black quarterbacks have had to shatter stereotypes to even get to this point. It took decades of persistence for them to get fair opportunities. Their resilience in the face of adversity is not just a story of struggle, but also of inspiration and hope. Expecting people to forget that history simply because things are improving is a weak attempt to erase the struggle that got us here.

Refusal to Acknowledge Progress

Whitlock’s exhaustion with Black excellence is not about a desire for fairness. It is about a refusal to acknowledge progress because that progress makes him uncomfortable. He ridicules the idea that every Black achievement should be celebrated. He compares it to mundane acts like combing one’s hair. He wants to reduce racial progress to a triviality.

Acknowledging the success of Black quarterbacks is not about victimhood. It is about victory. It is about showing young Black athletes that leadership is for them, too. Intelligence and decision-making at the quarterback position are not the exclusive domain of white players. It is about letting young Black kids see that the roadblocks that once kept their predecessors from playing quarterback are being dismantled piece by piece. The narrative has changed, but the fight to keep the doors open continues. Pretending that race no longer plays a role in the perception of quarterbacks only benefits those who never had to fight for their place in the first place.

Why Progress Should Be Recognized

Progress is not just about individuals succeeding. It is about the transformation of a system that once sought to suppress them. Every Black quarterback who steps onto the field carries the weight of those who were denied the opportunity to do so. Every victory is a declaration that the old barriers were unjust and that those who perpetuated them were wrong.

Black quarterbacks do not need a pat on the back. They need the history of their exclusion remembered so that no one ever dares to rewrite the past to fit a more comfortable narrative. Acknowledging progress is not to say that the struggle is over. It is to recognize that the fight was necessary and bore fruit. It is to ensure that the next generation understands where they stand in the lineage of those who refused to be sidelined.

Jaylen Hurts’s winning a Super Bowl matters, and Patrick Mahomes’s winning multiple Super Bowls matters. The league has gone from a time when Black quarterbacks were not allowed to exist to now having two Black quarterbacks as consensus top picks in the draft. That matters.

To erase the need to acknowledge progress is to side with those who resisted it. It is to accept the lies that were told to keep Black men out of leadership positions in the NFL. Jason Whitlock is exhausted by Black excellence. That is his burden to bear. Those who understand history know that progress is worth acknowledging. Progress should not be ignored because it was denied for too long.

The work is not finished. It never is, but it must always be honored.