Gatekeeping, “Statewide” Work, and Black Kids in Washington

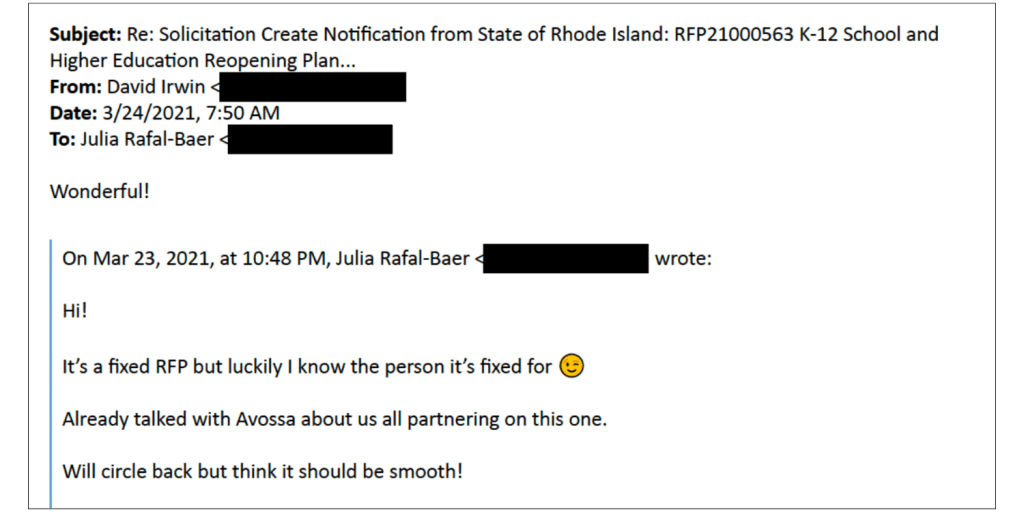

Somebody in Rhode Island hit send on an email that most people in education politics only say out loud behind closed doors.

“It’s a fixed RFP, but luckily I know the person it’s fixed for 😉.”

That one line sat at the center of a three-year investigation into how a multimillion-dollar contract to “support schools” during the pandemic was awarded. The attorney general finally came out and basically said, yes, the process was manipulated, yes, the rules were bent, no, we do not have clean enough evidence to prosecute anybody. Everyone walked away claiming there was “no wrongdoing,” even as the report admitted that the procurement rules had not been followed.

The emoji told the truth more than the official statements did.

I read that story and couldn’t help but think about Washington state. Could not help thinking about Black students in King and Pierce County, and about the way folks keep telling Black led organizations that their work is “not statewide enough” to sit at the big table.

It is very easy to look at Rhode Island and pretend that kind of thing only happens somewhere else. It feels safer to believe that our systems in Washington are cleaner, more ethical, more enlightened. It’s reassuring to think that we’ll never see anything “fixed” here.

I do not believe that story.

What “Statewide” Really Means

People throw “statewide” around as if it were a holy word.

Funders and agencies love the phrase. It sounds neutral. It sounds fair. It sounds like everybody in the state has the same access to support.

When you are talking about Black kids in Washington, that word does not mean what people think it means.

Most Black students in this state live in King and Pierce County. Those are the districts where the opportunity gaps are deepest, where special education outcomes for Black students look like a warning siren, where families are grinding every day just to get basic services honored. If an organization has done deep, consistent inclusion work in King and Pierce, that is not a limitation. That is strategy.

Instead of asking, “How many Black students are you serving, and what has changed,” people hide behind a different question.

“Have you done this work statewide?”

The way that question is used feels less like quality control and more like gatekeeping.

How Gatekeeping Works Without Saying The Quiet Part

Rhode Island gave us the cartoon version. Somebody literally wrote “fixed RFP” with a wink emoji.

In Washington, the script is cleaner. The game is not different.

You usually will not find an email that blunt. You get something like this instead:

- RFPs that quietly require “statewide experience” that only existing large vendors have

- Timelines so short that only people who knew the RFP was coming can respond.

- Scoring systems where “prior contracts with the state” is worth triple the points of “community trust” or “innovation for marginalized students”

- Definitions of “qualified” that read like the resume of one or two national firms

Nobody types “fixed.” Nobody adds the emoji. The result is the same. The circle stays small. The same consultants eat. The same organizations get to claim they are “driving equity,” even while the numbers for Black kids remain stuck.

When Black led organizations show up with receipts from King and Pierce County, the bar shifts. Suddenly, the issue is not whether work with Black students has been effective. The problem becomes whether that work has been replicated in every corner of the state, including areas where there are few Black students to begin with.

That is not an equity critique. That is a control tactic.

Who Gets To Define “Serious” Work

Examine the leadership that typically sits around these decision-making tables.

You see the same networks, the same career paths, the same professional conferences. You hear the same language about “systems change” and “capacity building.” You see people move from national nonprofits to state agencies and then to consulting firms, and then back again. The titles change. The worldview rarely does.

These are the folks who decide what counts as “serious” work.

They trust:

- A white paper more than a parent testimony.

- A national pilot in ten states more than a five-year track record in one county

- A big firm’s “evidence-based framework” more than a Black led program that actually moved graduation or employment outcomes.

When a community-rooted model emerges that does not fit their template, confusion ensues. Skepticism shows up fast. The question is not, “Are Black kids doing better with this approach?” The question is, “Does this look like what we are used to buying?”

If it does not, the easiest way to push it aside is to say, “You have not done this statewide.”

Washington Is Not Immune

Washington has its own history of sloppy or questionable contracting in the education sector. Audits have criticized districts for entering into contracts with vague public benefits, for disregarding evaluation scores and awarding work to less qualified vendors, and for weak controls that leave the door open to favoritism.

Those findings are public. People can pretend not to know about them. The record is right there.

Once you accept that favoritism and insider advantage are possible in any system, it becomes tough to argue that inclusion work for Black students is magically protected from those same dynamics. The same people, the same processes, and the same vendors show up across different contracts.

If leadership continues to rely on the same small circle of partners, even when data for Black students remains flat or worsens, it is fair to ask why. It is fair to wonder who the work is centered on.

What It Means To Take Black Kids Seriously

Taking Black students seriously in Washington means facing a simple reality.

If your “statewide” equity strategy does not put serious weight in King and Pierce County, it is not about Black students. It might be about optics. It might be about spreading money around so every region feels included. It might be about preserving relationships with long-time vendors. It is not about the children who are actually carrying the heaviest burden inside this system.

Community-rooted organizations that have lived in this work, who have walked into IEP meetings with families, who know which schools follow through and which ones stall, are not “nice to have.” They are essential.

That does not mean every Black led group is perfect or deserves automatic funding. It does mean the default cannot always be “give it to the same national partner again,” while local programs that are actually changing outcomes get told to come back once they are more “statewide.”

Fixed For Who

The question that lives under every RFP, every “competitive” process, every panel scoring rubric is simple.

Fixed for who?

Fixed for whose comfort, whose career, whose network, whose idea of what “real” work looks like. Fixed for which kids, which families, which communities?

When a Black-led organization that has been operating in King and Pierce County is told it is not statewide enough, that answer says more about the system than it does about the organization.

If the people at the table cannot see that, the problem is not our lack of experience. The problem is their lack of imagination and their unwillingness to relinquish control.

Our work has never been about flattering gatekeepers. Our work focuses on Black students in Washington who deserve more than business as usual, dressed up in equity language.

The contracts, the criteria, and the leadership need to catch up to that reality.