Equity Without Cash Flow Is a Lie

A community organization wins a competitive grant. The email arrives like a small verdict of worthiness. There is celebration, there are screenshots, and there are phone calls to the people who kept the lights on when nobody was watching.

The celebration lasts about ten minutes.

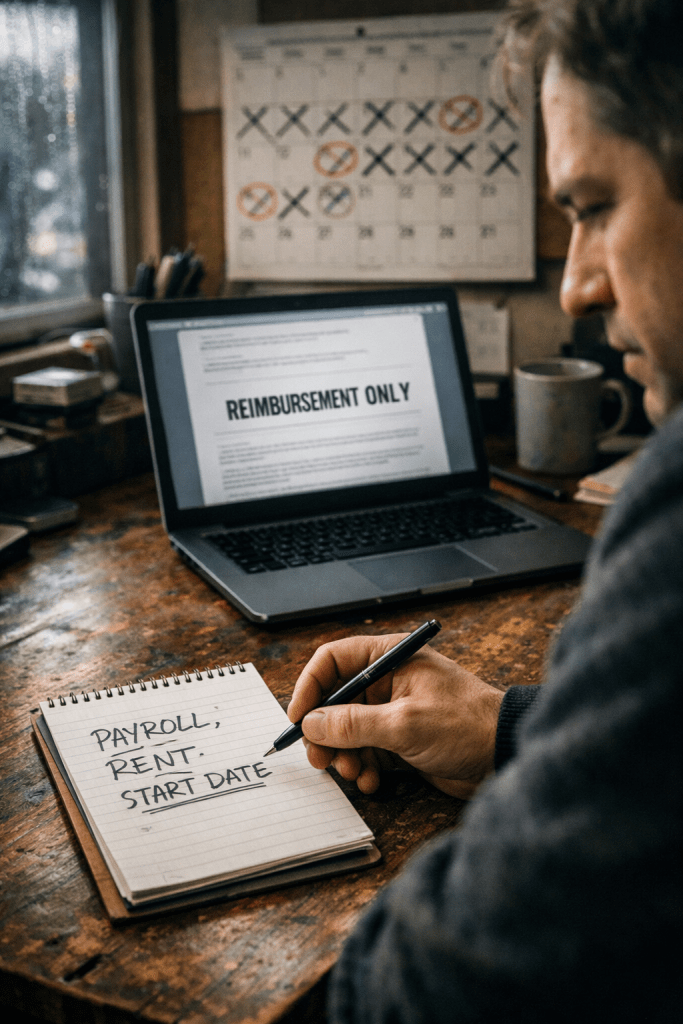

Then someone opens the contract and sees the part that never makes the press release: reimbursement only.

That phrase is where a lot of “equity” work goes to die quietly. The program is approved, the budget is “awarded,” and the public agency gets to say it funded the work. The people who actually have to do the work are told to front the money, cover the payroll, float the rent, buy the supplies, carry the insurance, hire the staff, and deliver the service first.

Later, if everything goes right, the government pays them back.

This is not a paperwork problem. This is not an administrative hiccup. This is a structural decision about who gets to participate in public work and who gets filtered out before the first client is served.

Reimbursement-only funding is breaking community organizations, then pretending the breakage is just the cost of “accountability.”

How reimbursement funding really works

Reimbursement models operate on a simple demand: pay first, get paid later.

An organization spends money to deliver a publicly funded service, then submits invoices and documentation to be reimbursed. The waiting period is treated like normal weather, as if everyone has the same coat.

Timelines look like this in real life:

- 45 days, if the system is smooth

- 60 days, if a signature is missing

- 90 days, if someone is out of the office

- 120 days, if the backlog becomes the policy

The model assumes providers have cash reserves, access to affordable credit, or leaders willing to personally carry the risk. It assumes the organization can operate like a bank.

That assumption is not neutral.

Who this model actually serves

Reimbursement-only funding works best for large institutions with financial padding: reserves, endowments, established finance teams, and low-cost lines of credit. They can float expenses without delaying payroll or cutting services. They can “comply” without bleeding.

Community-rooted organizations do not have that luxury. They operate closer to the ground, where money comes in tight, where staffing is lean, where every dollar is already assigned to a need that is not theoretical.

This is not about competence. This is not about who can follow the rules.

This is about liquidity, which is just a polite word for who gets to breathe.

The damage nobody tracks

Reimbursement-only funding produces harm that never shows up in the final report, because the report does not ask the questions that would reveal it.

Here is what happens while the public agency is “processing”:

Payroll gets strained. Hiring gets delayed. Positions get frozen. The work gets done by fewer people, for longer hours, under more stress, with less support.

Programs start late. Enrollment gets capped. Services get reduced. Families hear “we’re funded” and still wait weeks, sometimes months, for the thing that was supposedly approved.

Leaders go into personal debt. Executive directors use personal credit cards to cover public services. They take out loans so the community does not feel the gap, then they carry that cost in their bodies, in their families, in their sleep.

People burn out. Staff leave. Directors step down. Organizations collapse. Those collapses get labeled “capacity issues,” as if cash flow starvation is a personality flaw.

The reimbursement model turns public service into private risk, then acts surprised when the closest providers disappear.

This is an equity issue, not an administrative one

Reimbursement does one thing with remarkable consistency: it pushes financial risk downward.

Risk moves away from the institutions with the most protection and toward the organizations closest to the need. The groups doing neighborhood-level work, the ones trusted by families who distrust systems for reasons history made rational, end up financing the state’s promises.

That creates an ugly sorting mechanism.

Organizations that are most embedded in the community are often the least insulated from delay. The organizations most insulated from delay are often the farthest from the daily consequences of policy failure.

The system rewards distance from the community, not proximity to impact.

Equity without cash flow is a lie.

The myth of accountability

Reimbursement is often sold as oversight. Pay later, verify first. Protect taxpayer dollars.

That argument collapses under basic scrutiny.

Receipts prove spending, not outcomes. Documentation proves compliance with a process, not delivery of meaningful results. Delayed payment does not prevent misuse; it punishes the organizations that are already doing the work correctly while they wait for the machinery to catch up.

Accountability is a real need. Reimbursement is a lazy substitute.

Real accountability looks like clear deliverables, transparent reporting, results-driven monitoring, and consequences for non-performance.

None of that requires starving providers.

What better funding actually looks like

Better models exist. They are not radical. They are practical.

Frontloaded startup disbursements. Pay at the start for staffing, setup, required compliance, and launch costs. Programs do not begin with invoices; they begin with people.

Milestone-based payments. Tie payments to delivery milestones, not the organization’s ability to float expenses. If the milestone is met, payment triggers automatically.

Small retainage, not survival holdbacks. Hold back a limited percentage for reconciliation at the end. Do not hold the entire contract hostage.

Clear days-to-pay standards. Publish timelines. Automate payment when documentation is accepted. Track “days to pay” as a public performance metric.

This is what it means to design contracts for real organizations, not theoretical ones.

The fear nobody says out loud

Public agencies worry about misuse. That fear is real.

Misuse is already managed through milestones, audits, site visits, documentation requirements, and clawbacks. The tools exist. The system chooses to make cash-flow deprivation the default risk strategy.

That strategy increases failure risk. Starved organizations deliver worse outcomes, not because they are dishonest, but because financial instability creates operational instability. The work becomes fragile.

Trust does not mean naivete. Trust means building smart guardrails without demanding that community organizations become involuntary lenders.

The cost of doing nothing

Reimbursement-only funding shrinks the provider pool. It rewards organizations that can float the state, and punishes those that cannot.

Fewer providers mean fewer options, less innovation, and more service gaps. Communities lose access while governments recycle unspent funds and call it efficiency.

Short-term caution becomes long-term expense.

The public ends up paying anyway, just not in the budget line where it is easy to see. The cost shows up in turnover, in crisis response, in missed prevention, in families falling through gaps that were “funded” on paper.

A direct ask to funders and policymakers

Pilot frontloaded or hybrid funding now. Not later. Not after another year of listening sessions where the same people explain the same harm.

Track and publish days-to-pay. Make payment speed a measure of performance.

Design contracts that match reality: payroll runs every two weeks, rent is due every month, and public service does not pause because Accounts Payable is behind.

Closing

Equity that requires personal debt is not equity.

If the work matters, the money has to arrive on time.