For years, Special Education in Washington has carried a quiet secret.

Students were not always identified because someone truly studied how they learned. Many were identified because they had low scores, and adults had run out of ideas.

If you were a Black boy who did not sit still, who questioned adults, who carried trauma into the classroom, you were often seen as a problem to be managed instead of a learner to be understood. The easiest place to move a “problem” was Special Education. The quickest path was the severe discrepancy model.

Now that path is being closed.

Washington is phasing out the old discrepancy model for identifying Specific Learning Disabilities and moving entirely to an instructional, data-based approach. For Thoughts Cost, this is not just a policy memo. This is something we have been advocating for since COVID flipped school into crisis mode and exposed what was broken.

This shift is not just technical. It is moral. It is about stopping the practice of hiding children inside labels.

What Just Changed

Under the old model, a student could be labeled SLD essentially because there was a big gap between their IQ score and their academic achievement. That gap was treated as proof of a disability.

This sounded scientific. It was not.

It ignored the quality of instruction. It ignored missed school. It ignored racism and bias. It ignored trauma. It ignored the difference between a student who cannot learn and a student who has never been taught in a way that fits them.

The new direction in Washington says:

- You must show that a student was given solid instruction.

- You must document targeted interventions.

- You must collect progress monitoring data over time.

- You must make decisions based on instructional response, not just test gaps.

In simple terms, schools must teach first, then evaluate. Not label first, then figure it out later.

How The Old System Helped Push Kids Into SPED

The severe discrepancy model emerged at a time when schools sought quick answers. A student is behind in reading. Test them. The score is low. The IQ is average. There is a gap. Call it SLD.

For many students, especially students of color, that gap did not come from a disability. It came from:

- Being suspended and removed from instruction.

- Sitting in classrooms where expectations were low.

- Teachers who were not trained in explicit reading or math.

- Trauma from housing instability, violence, or illness.

- Language differences were treated as deficits instead of assets.

During COVID, this became painfully obvious. Entire districts were struggling to reach students online. Some kids had no consistent internet. Some shared laptops. Some lived in survival mode. Yet when academic scores dropped, the system was still ready to label the child rather than interrogate the conditions.

Thoughts Cost has been saying since those early pandemic days:

You cannot call it a disability if you never gave the student a fair shot at learning.

The Disciplinary Trap

There is a pattern that every Black parent and community educator knows, even if it never appears in a technical report.

A student is “disruptive.”

Teachers feel overwhelmed.

Office referrals pile up.

The student is sent out of class so often that they fall behind in reading and math.

Once the data shows they are far below grade level, someone says, “Maybe there is a disability.”

The behavior created the exclusion. The exclusion created the gap. The gap then gets rebranded as SLD.

The new model makes it that much harder to pull off. Behavior issues, cultural clashes, or adult discomfort cannot serve as a substitute for instructional data. Schools will need to show:

- What was taught?

- How was it taught?

- What supports were tried?

- How the student responded over time.

This forces an uncomfortable truth into the light. Many students who were pushed into Special Education were not struggling because their brains were broken. They were struggling because the system failed them.

Why This Matters So Much For Black Students

When you look at who gets labeled, who gets suspended, and who ends up in segregated classrooms, you see the same pattern over and over.

Black boys get:

- Less patience.

- Less benefit of the doubt.

- Less culturally responsive teaching.

- More discipline.

- More isolation.

Once labeled, that SLD tag follows them into every classroom, every IEP meeting, every conversation about what they are “capable” of. It shapes expectations. It shapes access. It shapes how others talk about them when they are not in the room.

Moving to an instructional, data-based approach does not magically fix racism. It does something important, though. It removes one of the easiest tools the system had for turning racial bias into permanent paperwork.

If you want to label a Black boy SLD now, you will need instructional receipts.

Thoughts Cost, Covid, And The Long Game

Since COVID, Thoughts Cost has been in classrooms, on Zoom calls, in IEP meetings, and in community spaces, asking the same questions:

- Is this really a disability, or is it a lack of access?

- Did this student ever receive high-quality Tier 1 instruction?

- Were interventions implemented with fidelity?

- Is this behavior communication, trauma, or resistance, not pathology?

We have been pushing:

- Data systems that track actual instructional response, not just test scores.

- Culturally sustaining practices that honor how Black and Brown students learn.

- Training educators to separate disability from adversity.

- Transition planning that does not trap students in low expectations for life.

This policy shift finally aligns the law with what we have been arguing in practice. It gives families and advocates language to say:

“Show me the data. Show me the interventions. Show me where you taught my child before you decided something was wrong with them.”

What This Shift Makes Possible

If Washington does this right, we will see:

- Fewer students mislabeled with SLD.

- More accurate identification of students who truly have learning disabilities.

- A reduction in the use of Special Education as a disciplinary closet.

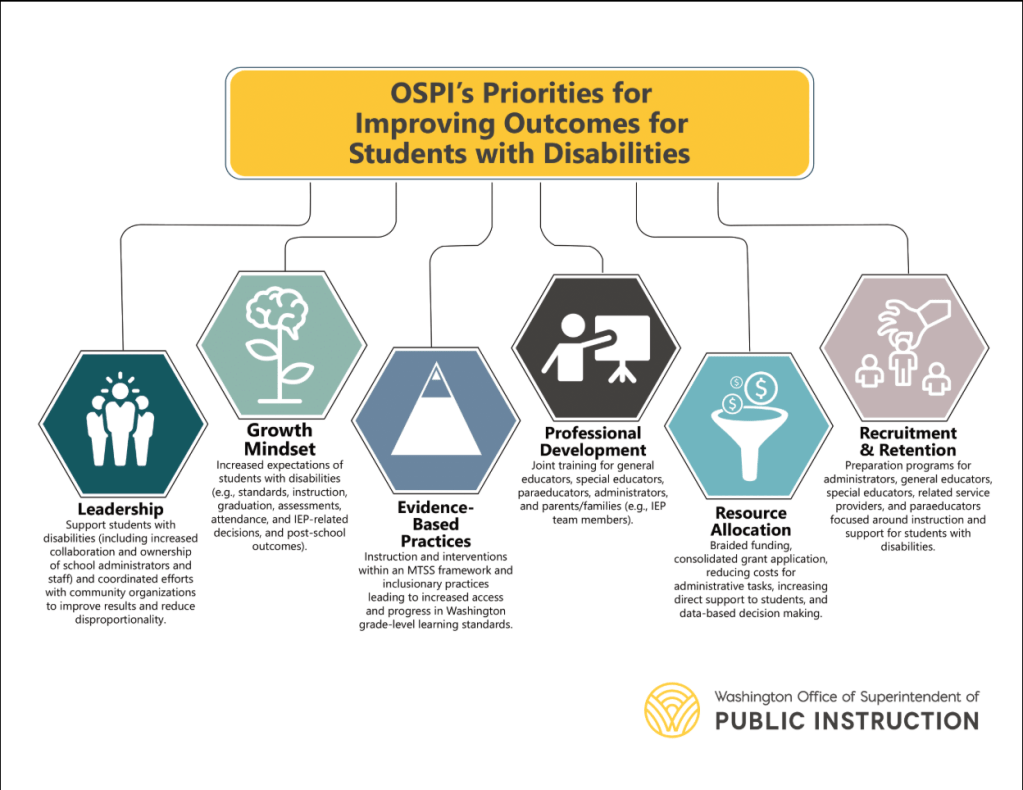

- Stronger MTSS systems that serve all students, not just those on IEPs.

- Better collaboration between general education and Special Education.

- A path for students who were misidentified to exit Special Education with dignity.

This shift is also an opportunity to repair harm. During reevaluations, teams will need to ask hard questions about previous decisions. How many students were placed because it was convenient for adults, rather than what was correct for the child? What can be done now to restore opportunities?

What Districts Need To Do Right Now

This policy change is not “just a Special Education thing.” It touches everything.

Districts will need to:

- Build or strengthen MTSS systems where Tier 1, 2, and 3 are real, not buzzwords.

- Train staff on progress monitoring, not just compliance paperwork.

- Audit discipline data side-by-side with SPED identification patterns.

- Bring families into the conversation as partners, not as signatures.

- Provide culturally responsive training so educators can distinguish racism from “noncompliance” and culture from “defiance.”

- Invest in tools and practices that make data usable, not overwhelming.

Thoughts Cost is positioned for this moment. This is the work we do every day. Not in theory, but side by side with families, teachers, and students navigating the system in real time.

This Is About Who We Believe Our Children Are

At the core, the shift away from the severe discrepancy model is a shift in belief.

Do we believe students struggle because there is something fundamentally wrong with them?

Or do students struggle because systems have failed to teach them, include them, and see them?

When a state moves from “wait until they fail enough to qualify” toward “teach, intervene, and then decide,” it is choosing to believe in instruction, in relationship, and in the possibility that students can grow when given what they need.

Thoughts Cost has been on that side of the line since the beginning.

This policy finally moves the system closer to where our communities have been standing all along.

Our message now is simple.

Teach them.

Please support them.

Collect the data.

Then tell the truth.